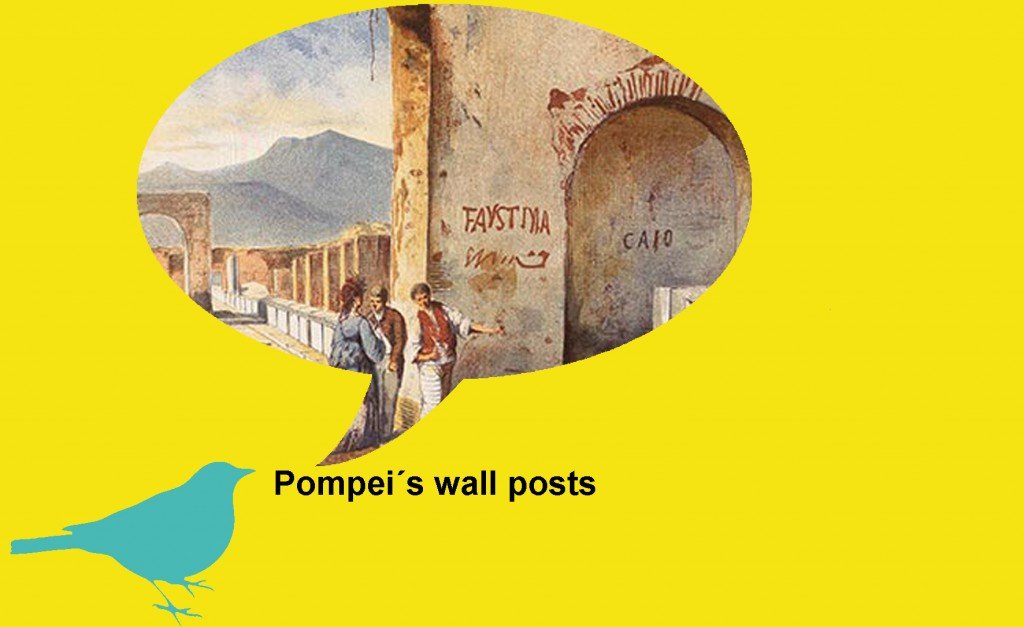

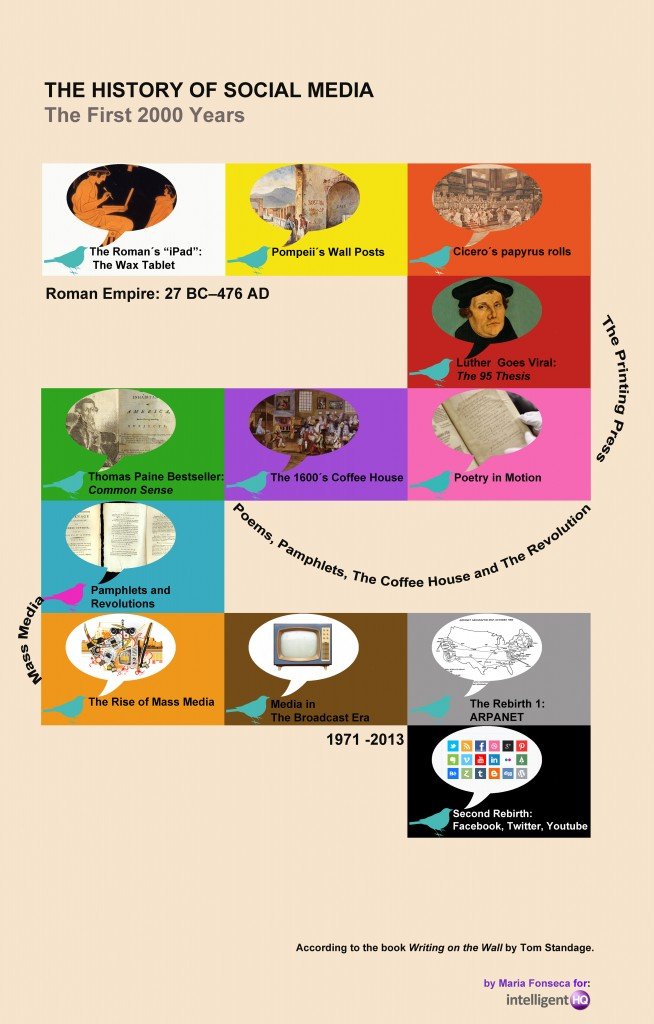

“Without gossip there would be no society” says Robin Dunbar as cited by Tom Standage in his newest book Writing on the Wall: Social Media – The First 2,000 Years that just came out last October. Tom Standage, who is the digital editor of The Economist and the author of other unorthodox narratives such as “A History of the World in 6 Glasses” and “The Victorian Internet” accomplishes with his last book, a quite astounding deed: To write the history of 2000 years of social media. And if you think that social media corresponds to “a group of Internet-based applications that came out of the Universe of Web 2.0, you are not sufficiently informed. To post a status on the wall, is not something that Facebook or Twitter have invented in 2006. Rather it is a very ancient activity that goes back to the classical era. He gives examples: “I made bread,” brags a roman on a wall in Pompeii. And “George Clooney’s” predecessor, Celadus the Thracian “makes all the girls sigh” writes another ancient scribbler. These posts could have been on Twitter or Facebook, but no, because the internet was not yet invented. They were inscribed as graffiti in the walls of Pompeii, or in wax tablets, the iPads of the Roman Era. And Standage adverts us to look at the past, by citing the thoughtful words of Cicero, the famous Roman politician and orator that lived more than two thousand years ago:

“Not to know what has been transacted in former times is to be always a child. If no use is made of the labors of past ages, the world must remain always in the infancy of knowledge, (Marcus Tullius Cicero).”

Standage´s point is that today’s social media environment is nothing else but an up-to-date repetition of something that goes back centuries and that is rooted in a deep desire human beings have for communicating with each other on a personal basis. Writing on the Wall functions as a chronicle of the history of information, looking at it as something that is constantly being reinvented spontaneously and organically. As such, the Social Media of nowadays, is actually not that different from what he calls the “Really Old Media”. What is remarkable is that both the “very old” system and the contemporary one, share many similarities such as being a two-way, conversational environment, where information is distributed horizontally along social networks, rather than being delivered vertically from an anonymous central source. Adding to this, both systems have their share of analysts that criticize fearfully the new trends that are being driven by changes in technology or any social invention, cautioning on the bad effects those new inventions can have on the minds and morals of people.

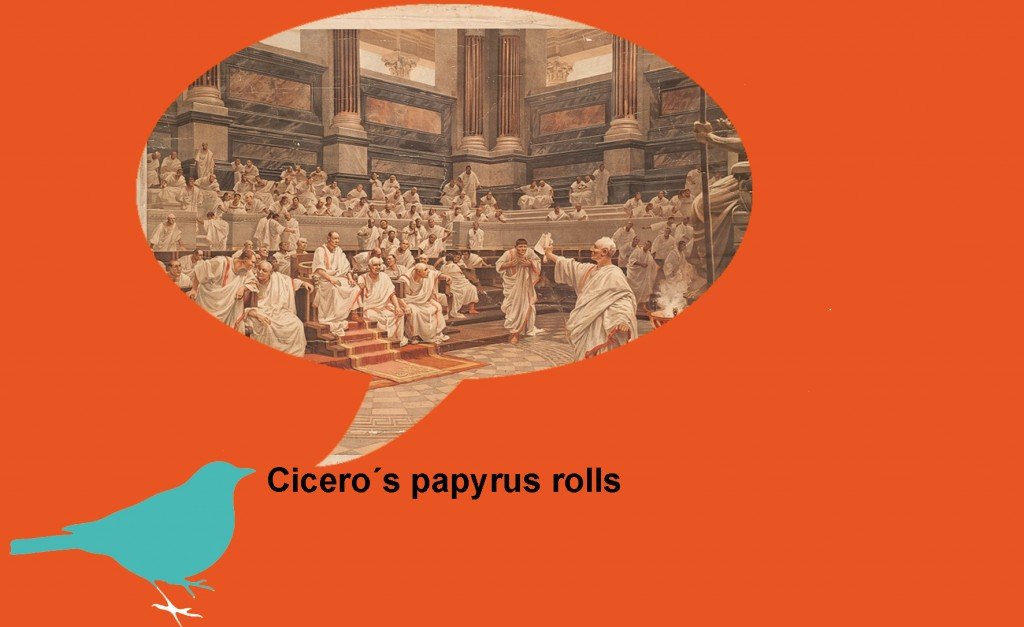

Standage begins by reviewing the development of writing from Babylonian cuneiform through Egyptian hieroglyphics and into Semitic, Greek and Roman alphabets. He then bumps into the first skeptic on innovation, who believe it or not was philosopher Plato, who though that writing was inferior to face to face dialog: “Spoken dialog is the natural way to learn” stated wise Plato: “Writing weakens your memory”. Then he moves into theRoman Empire where systems of communication and information, such as wall graffiti, erasable wax tablets and papyrus rolls functioned as informal messaging systems that coexisted with the formal ones such as the Acta Diurna, the Roman Daily gazette. The Acta Diurna used to be fixed to the walls of the Forum and finished with the expression “publicare et propagare” that so much resembles the share or tweet of nowadays. Tom Standage gives us creative details of the Roman Social Media process: “If you were a wealthy Roman who wanted to read the news over breakfast, you might send a scribe down to the forum to jot down excerpts from the daily gazette, or acta diurna, onto one of these tablets. You could then copy highlights from the news to your friends: the text would be copied onto papyrus rolls and taken to them by messenger. They might then copy those news reports, in turn, to their own friends, adding their own comments or analysis. This is how the Roman social-media system worked.”

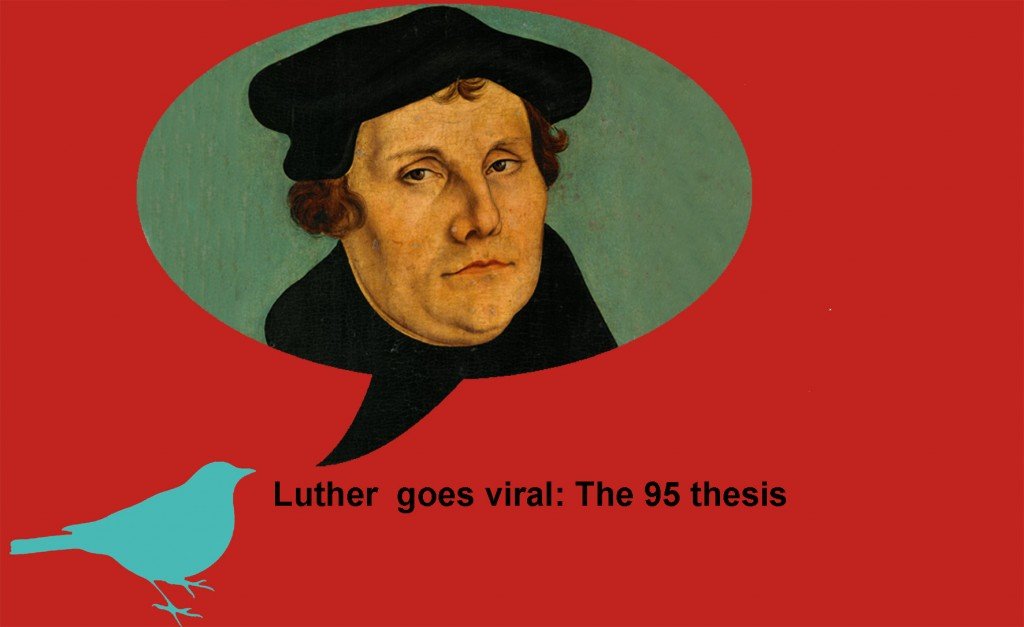

This fascinating tale arrives then at another crucial moment that happens in the city of Mainz during 15th-century through the industrious hands of Johannes Gutenburg, the inventor of the first printing press with mechanical movable types. Finally, a page that would have taken hours to copy is now be reprinted in seconds. Books could be crafted easily, and a new era was created that would permanently revolutionize the structure of society. One of the first printing sensations will happen in 1514: On 31 October 1517, Luther posts his Ninety-Five Thesis, which he had composed in Latin, on the door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg. The same day, he sent a hand written copy to the archbishop. In a lapse of a second, his thesis, that criticized the system of indulgencies, created turmoil: they would be translated to German, and dozens of copies would be printed through the movable type press, spreading his ideas throughout Germany in two weeks, and within two months throughout Europe. This would give way to a widely known “revolution”: the Protestan Reformation. Standage invites you to see the parallels between Luther’s pamphlets triggering the Reformation and the similar disaffection voiced on Facebook before the Arab Spring Revolution, happening in Tunisia and Egypt nearly three years ago.

Another social media platform that happened during 17th Century England was the coffeehouse that had a remarkable quality: it enabled the gathering of all types of people, that transformed it into an open forum for the exchange of ideas. The coffeehouses were “crucibles of innovation,” where scientists and intellectuals would regularly meet to discuss theories, conduct experiments and hold lectures, which generated incredibly fruitful intellectual results. That was the case of Newton’s Principia Mathematica, written in order to settle a coffeehouse argument between Wren, Hooke and Halley! Stavange compares the intellectual and commercial development enabled by coffeehouses in the 17th century to the possibilities for innovation and the dynamic exchange of ideas provided by contemporary social media platforms. Who was born before the nineties can´t escape identifying with the social media forum which was the one of the coffeehouse which is my case as well. Living in Lisbon during the nineties, a teenager, I had no Internet yet. We had books, newspapers, magazines, radio, the cinema and of course television. And then, we had the coffee house. Everyday I would go to Sissi, my favorite one. There I would find my friends and we would chat all evening navigating from the gossip of the day to the latest political news, which would always raise heated debates and opinionated views. Expectedly,the Coffee House was subjected to sharp criticism since its origin :“[The coffeehouse] admits of no distinction of persons, but gentlemen, mechanic, lord and scoundrel mix, and are all of a piece.” says Samuel Butler, whereas Anthony Wood writes during the 1670s: “Why doth solid and serious learning decline, and few or none follow it now in the university? Because of coffeehouses, where they spend all their time.” Another critic was Thomas Fuller a 17th-century clergyman that argued that the pamphlets read in the coffeehouse “cast dirt on the faces of many innocent persons, which dried on by continuance of time can never be washed off”. Back in time notable intellectuals criticized the “social media” forums of 17th century, in a remarkable similar way to contemporary debates surrounding the use of social media.

As the printing press flourished, pamphlets and books were printed and distributed widely becoming the most important vehicles of various revolutions. In England the government attempted to control books, pamphlets and printers, often by chopping off hands or execution. Famous pamphlets that “became viral” were John Milton´s Areopagitica, written in 1644 which was an eloquent appeal for Freedom of Press. Another was Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, written in 1775-76. Common Sense instigated the population of the America´s thirteen colonies to declare and fight for independence from Great Britain. The pamphlets were written in a clear and simple style that was comprehensible to the common. It was sold and distributed widely and read aloud at taverns and meeting places. It sold so well that it transformed Paine into a best selling author in the whole world.

The shift from “really old media” to “old media” finally happened in the midst of the Industrial Revolution, through the invention of the steam press and the telegraph. The former meant that it was finally possible to print thousands of copies of newspapers daily. Standage establishes a particular date as being the one that marks the beginning of a new era and a shift of paradigm : 1831, the date when the penny newspaper was invented in New York. The influence of the telegraph concerned the velocity of transmission of information, which helped to make newspapers more captivating and profitable. Soon a quick wave of technological evolution would follow, from radio telegraphy to radio telephony and finally television. But what happened was that the source of mass media became centralized, and controlled by the hands of very few.

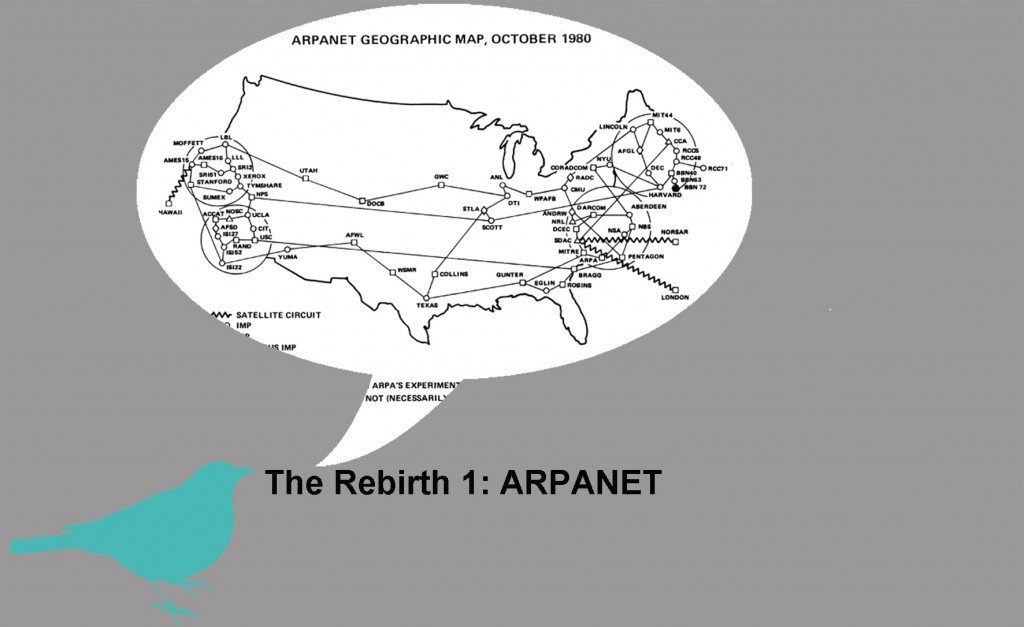

The last phase of this story came with invention of ARPANET, the Internet, and finally the world of social media that we all so familiar with.

Tom Standage book is based on a simple tactic that impregnates the whole book with wit: the application of the Internet jargon to various crucial stories of our distant past. But the writer´s central argument is actually very thought provoking: he suggests that mass media, the means of distributing information that we have become so used to, particularly in the last century, are actually a deviation from a more “natural” and organic way of distributing information. Now that centralized industrial processes have given way to widely distributed, technological ones, where any individual with access to a computer can publish and opinionate, we are reinventing old ways of doing things. What this means is that presently the nature of life online is similar to the one of the 16 hundreds coffee shop. “Writing on the Wall” compels the reader to reflect about the media we are using in our daily lives in terms of the role social media invite us to perform: that role is the one of active contributors, that share, comment and reflect about what they like and don´t like in the world or their private lives, with friends and others alike.

Maria Fonseca is the Editor and Infographic Artist for IntelligentHQ. She is also a thought leader writing about social innovation, sharing economy, social business, and the commons. Aside her work for IntelligentHQ, Maria Fonseca is a visual artist and filmmaker that has exhibited widely in international events such as Manifesta 5, Sao Paulo Biennial, Photo Espana, Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Joshibi University and many others. She concluded her PhD on essayistic filmmaking , taken at University of Westminster in London and is preparing her post doc that will explore the links between creativity and the sharing economy.