“A storm of change is coming” write Robert Scoble and Shel Israel in their latest book The Age of Context, by paraphrasing a caped man that shows up suddenly, in a 2005 Batman film, to deliver to Commissioner Gordon a cryptic message: a terrible tempest is about to overthrown Gotham City. And as the guy shows up, he also disappears in a glimpse of a second. The storm comes, and it provokes a hell that lasts the two hours of the film. But by the end of it, when peace is finally restored, the inhabitants of Gotham City, discover a better place to live. With futuristic optimism, the authors use Batman and Gotham City to introduce to the reader that a new era is about to arrive to our lives. That era will change life as we know it in such a radical way, that it will look for a while that we are living within a thunderstorm. But just as Batman´s fable ends up in a shinny happy way, the authors suggest that those changes can be for the best. And what era is that era they are talking about?

The Age of Context.

Robert Scoble and Shel Israel are two authors that became known after their pioneering book on blogs and social media in general, entitled Naked Conversations, published in 2006. Naked Conversations anticipated most of what would happen to social media, as it persuaded and advised businesses to ponder the blogosphere as an inevitable and extremely useful tool to advertise products.

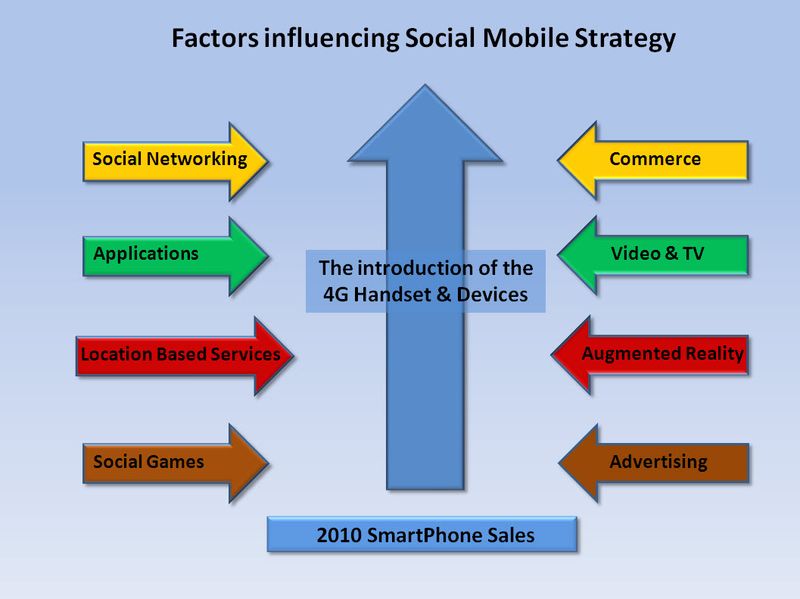

In their new book the authors focus now in analyzing a new era, that is being shaped by the jointed effort of five new forces that were enabled by the invention and development of the cloud computing infrastructure. These forces, which are social media, mobile devices, big data, sensors and location-based technology, form a new generation of personalized technologies that will transform very quickly virtually every aspect of our lives. As the authors say: “Together, they have created the conditions for an unstoppable perfect storm of epic proportion.” The crucial question is how to adapt to these changes.

The Age of Context offers the reader a kaleidoscopic and encyclopedic description of the state of technology in 2013, looking across a broad number of fields: healthcare, transportation, the electronic home, urbanization, mobile devices, marketing, and understanding customers. The book portrays a world to come (and already here) that is shifting and being shaped by the idea of Contextual Computing. Contextual Computing, which was first described by Georgia tech researchers Anind Dey and Gregory Abowd a decade ago, is the most recent development in the progression of technology. It refers to the fact that technologies are starting to “understand” things about you and your environment – things like your schedule, your location, your heart rate, and reacting to these, in a very similar way to the human brain. The main concern about these technologies is privacy: the reason they can do such amazing things is because they’re gathering more and more information about us.

The book is divided in 12 chapters that cover a broad range of issues. In Chapter 1 the authors details the five forces. They refer how Social Media is the essential tool of the context era : “it is in our online conversations that we make it clear what we like, where we are and what we are looking for”. They also analyze how data is the driving force, the “oxygen” for the age of context. “Data now is named big data because the amount that has been accumulated is so much, and it continues to expand.” The crucial issue here is to look at big data through a different lens, focusing on the “the miracle of little data” which is the data we extract to ourselves, on a personal basis, and what we do with it. If big data can be intimidating, tiny bits of data taken on an individual level, can empower us into becoming smarter, creative, and productive.

In chapter 2, the reader is introduced to the wearable computers through various stories, starting from the famous Google Glass story. As everybody knows, Google Glass is a wearable computer with and OHMD (optical head-mounted display) that is being developed by Google in the Glass project. In chapter 3, entitled The costumer in Context, Scoble and Israel present us with a number of contextual technologies, that aim to bring back the past experience of personalized shopping. That is the case of company Uber, that can dispatch a car to pick you up before you request it, or VinTank, that predicts who are the wine fans about to enter Napa Valley, and works with their winery partners to send them exclusive vouchers and offers. These “right-time experiences” will start to deliver what you want when you want it.

Chapters 4 and 5 speak about the huge changes happening on the car industry due to the new mobility preferences of a recent generation of consumers. Now, contextual technologies can reshape cars according to individual preferences in seating position, gas stations, restaurants, how they can brake automatically to prevent a crash, or turn on windshield wipers when it starts raining. But the flip coin issue raised here is how third parties such as insurance companies, the government, and used car buyers can use this data. On the other hand, consumers are changing and younger people increasingly prefer phones to cars. Self-driving cars, which use contextual technologies to sense the environment around them, can be safer and more energy-efficient.

Google is already testing its driverless cars, which use an expensive rooftop spinning device with LIDAR systems installed (LIDAR is a remote technology that measures distance by illuminating a target with a laser and analyzing the reflected light). That technology can “see” lane markers, signs, people, and cars. Driverless cars can be particularly fascinating but to engage mainstream consumers, they’ll have to become affordable, overcome the “freaky factor”, and operate through government regulations.

Google is already testing its driverless cars, which use an expensive rooftop spinning device with LIDAR systems installed (LIDAR is a remote technology that measures distance by illuminating a target with a laser and analyzing the reflected light). That technology can “see” lane markers, signs, people, and cars. Driverless cars can be particularly fascinating but to engage mainstream consumers, they’ll have to become affordable, overcome the “freaky factor”, and operate through government regulations.

In chapter 6, the authors describe the type of humans living in the age of context: the New Urbanists. These are a group of sophisticated urban people that are financially independent, found of smartphones but that rarely use cars. Ecologically aware, they are interested in participating with local government to improve their urban environments, by using plans and 3D models shared in the cloud. The maker movement, popular in cities, also follows this same spirit of community improvement.

Chapters 7 describe the great changes context technologies are introducing to our health and wellbeing through stories of how health sensors, gadgets and social networks are becoming big tendencies. The cases range from pills with sensors that can tell if you’ve taken them, to the Fitbit and Nike+ Fuelband, or the FAST scanner that can detect cancer cells and test treatments on them. Another example is the story of Dr. Jennifer Dyer, a child endocrinologist in Columbus, Ohio who has designed a Serious game mobile app that encourages teens to note when they take their medicines, eat right or exercise, through taking care of a virtual pet dog named Cooper. The challenge will be convincing current investors to abandon the status quo in favor of better health systems. Chapter 8 introduces to the reader the wearable technologies with examples such as bras that give electrical shocks to rapists or detect cancer, to t-shirts that can charge devices. Possibly wearable technologies will become more and more integrated with our bodies, eventually leading to implants. These will make us healthier, more informed, aware, and more creative.

Chapter 9 speaks about PCAs: Your New Best Friends, the Personal Contextual Assistants. PCAs are open, cloud-based mobile platforms that communicate with other apps in order to figure out and anticipate actions you might want to take. For example, they can message coworkers that you’re running late, suggest you drop by your favorite shopping center for a particular sale, or schedule a mortgage payment. The examples given are Google Now, EasilyDo, Atooma, and Lola by SRI.

How will your home be in the age of context? That is what chapter 10, named No Place Like the Contextual Home, tries to predict. The wonderful contextual home has devices that communicate with each other and with us to make things safer and more sustainable. “Smart” door locks, windows, bathroom mirrors, toothbrushes, and refrigerators will figure out when we want things from them. TVs will suggest content depending on who’s watching, and robots will become more abundant.

Chapter 11 anticipates a new advertising era, calling it Pinpoint Marketing. Pinpoint Marketing offers the consumers things and services based on where you are, what you’re doing, and what you might do next. The problem here will be if contextual technologies start to guess your mood and share this information with others.

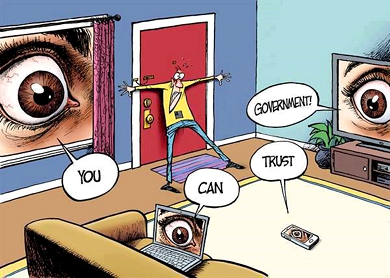

The last chapter points to the reader the fundamental loss arising from this new era: privacy. As Scott McNealy, the cofounder of Sun Microsystems says: “You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.” As the conflict between security and privacy isn’t likely to be resolved anytime soon consumers will definitely prefer companies they trust. That means companies that use terms of service with plain and trustworthy language, and other companies that provide the ability to “go private” or turn off tracking for a while, and not assuming we want to share information with others. The authors opinion is that the benefits from contextual technologies surpass the loss of privacy and personal information. “We believe that greater transparency by businesses and government will lead to higher rates of customer and citizen participation.”

Compared To Upcoming Obamacare Data Collection Efforts”

by J. D. Heyes

The book finishes with an epilogue that transports the reader to a splendid future: Reunion 2038. In 2038, Scoble and Israel are now extremely rich, as their book, The Age of Context, published 25 years before, was a major success. Scoble lives in a two-story house equipped with the most contextual technology that anyone could possibly imagine. As Google Glass is way past, he wears now “Google everywhere” to monitor the temperature of the water of his shower, through a simple thought.

Scoble and Israel´s futuristic fable delivers a warning for positive thinking: “At the end of the day, the technology has always been and always will be just a set of tools for people to use or abuse as they see fit. We can gush about the virtues, or agonize about the dangers until we turn purple”. What the Age of Context, will look like 25 years from now, they advice, is really up to us.

Maria Fonseca is the Editor and Infographic Artist for IntelligentHQ. She is also a thought leader writing about social innovation, sharing economy, social business, and the commons. Aside her work for IntelligentHQ, Maria Fonseca is a visual artist and filmmaker that has exhibited widely in international events such as Manifesta 5, Sao Paulo Biennial, Photo Espana, Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Joshibi University and many others. She concluded her PhD on essayistic filmmaking , taken at University of Westminster in London and is preparing her post doc that will explore the links between creativity and the sharing economy.