A very interesting side phenomenon about the sharing economy is how it “touched” and impacted cities in a profound way. Large massive platform like Airbnb are, in a certain way, an immense “facebook” … of every single home in a specific city… fostering a whole new set of values to the “business of hosting”, swiftly moving away from the impersonality of hotels, to the intimacy of the local home. On the other hand, platforms like Uber revolutionized how transport operates in urban centres, enabling a massive amount of private drivers and cars, to compete with established industries such as the taxi one. These 2 big companies produced a uniquely “urban phenomenon” that impacts the city in novel ways. The sharing city!

The city as a sharing city, has been part of the ethos and ideology of the sharing economy from its inception, that we can trace back to a key year, 2008, the year Airbnb was created. One decade ago, the sharing economy was viewed with high hopes and strong doses of idealism. On the wake of the financial crisis, many looked at this new phenomenon in economics, as a possible way of sorting out the problems of traditional capitalism, particularly in terms of its negative impact on the environment and increasing inequality.

From the beginning, the city, became as well an important actor in all the ideology surrounding the sharing economy. The Sharing Cities Network, a project launched by shareable, in 2013, became an important advocate of the idea of the sharing economy applied to cities. The network described itself as a “a grassroots network for sharing innovators to discover together how to create as many sharing cities around the world as fast as possible” and it developed the narrative of the sharing economy as a transformational global movement founded on inclusive sharing and support for the urban commons to address social justice, equity, and sustainability. According to its founders, the sharing cities network “encourages actors to replicate trans-local experiments through face-to-face and digital interactions in multiple cities simultaneously, that connect diverse stakeholders including individuals, community groups, sharing enterprises and local governments. ” (Luna, 2013)

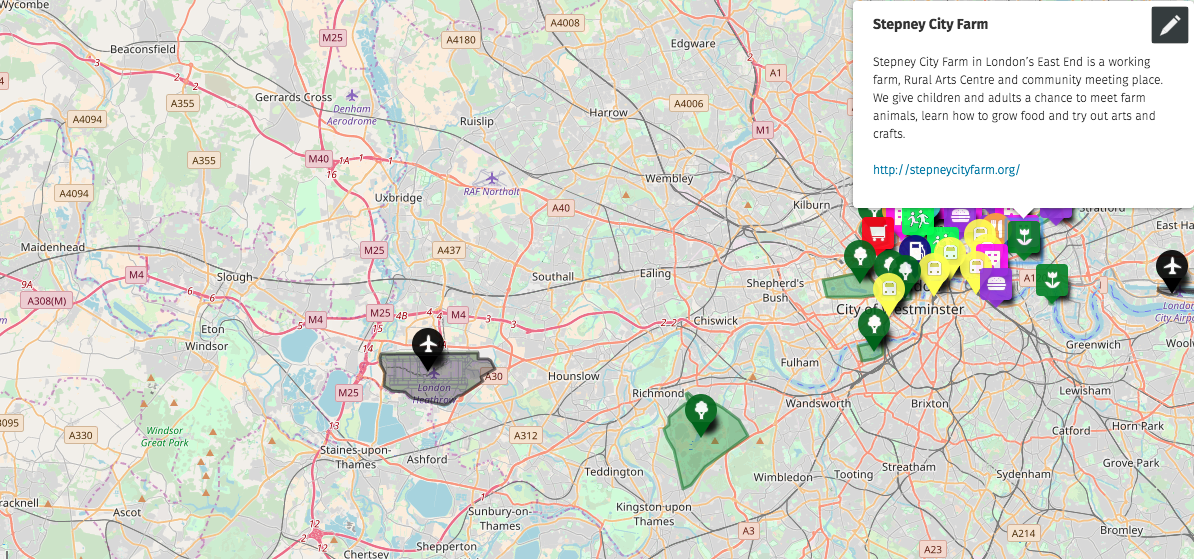

One of its first initiatives was the Sharing Cities MapJam, held between 12–26 October 2013, with a target of mapping the sharing economies of 25 cities supported by local teams . Shareable used its website and newsletter to promote the first MapJams, which were very successful. Following the MapJams success, Shareable ran a crowdfunding campaign and raised $54,000 through small donations from supporters.

Some cities quickly picked up on the attractive narrative of sharing, constructed as a peer to peer movement that looked for alternatives to the usual story of cities depending on centralized government and/or big banks and where hierarchical power was the one who had the power to produce change. Seoul was one of the first cities to embrace this concept, followed by Amsterdam, branded as Europe’s first named sharing city in 2015.

“Europe’s first Sharing City, Amsterdam, has convened a network of ambassadors from the commercial, government and knowledge sectors to develop a program of activities to support the local sharing economy and pilot a range of projects.”Miller 2015

A positive point of the sharing economy, was actually how it triggered the adaptation of its principles to cities, thus setting the ball rolling for the building of a narrative of the city as a sharing space, that would reinvent once again connection and community. In an article written in 2018 by McLaren, D. and Agyeman, about the emergent transformation of cities and regions in the innovative global “Any meaningful concept of Sharing Cities must go beyond the “sharing economy”, and explore approaches that are more cultural than commercial, more political than economic, and that are rooted in a broad understanding of the city as a co-created urban commons.”

The business of “sharing”

Quite paradoxically, big sharing economy companies like Airbnb and Uber, have build on the idea of the sharing city, as a way to brand and grow their businesses. From their onset these two companies had access to large investment, which allowed them to leverage network effects and urban clustering through two-sided marketplaces. Unfortunately, this was not done with the best intentions. As RSA researcher Bhrmie Balaram noted on a blog post “as these companies have scaled, they have found it difficult to sustain their initial social value.”

Another study done by Darren Sharp (2017) mentioned how “These commercial sharing platforms continue to disrupt legacy services, raise tensions between private and public sector interests, intensify flexible labor practices, and put pressure on rental vacancy rates.”

In his study, Sharp gives the example of how Airbnb, while embracing the rhetoric of aiming to support the “middle class” used massive amounts of money to mobilise hosts to influence urban regulatory regimes, when facing growing criticism pointing out how commercial home sharing was profoundly impacting housing availability. Over the past 5 years, this phenomena has happened in various urban centres, and a recent example is Lisbon, where raising levels of tourism, led the widespread adoption of Airbnb as a hosting service, which provoked the eviction of massive number of locals living in central Lisbon.

In San Francisco, when facing a similar problem, Airbnb spent over $8 million to defeat the Proposition F, a ballot measure launched in 2015, that would toughen regulation on the short-term rental of residential apartments and homes.

Nicole Derse from 50+1 Strategies who co-led the “No on F” campaign described how that money was used to fund a sophisticated blend of mixed media advertising, door knocking and host activation:

“The campaign had all the modern bells and whistles you’d expect of an effort backed by a Silicon Valley giant. Still, we also ran one of the most aggressive field campaigns San Francisco has ever seen. Over the course of 11 weeks, our staff and volunteers knocked on more than 300,000 doors, made some 300,000 phone calls and had over 120,000 conversations with real voters. We got more than 2,000 small businesses to oppose Prop. F. In fact, our Airbnb hosts took the lead in this campaign, hosting house parties, organizing their friends and neighbors, and leading dozens of earned media events.”

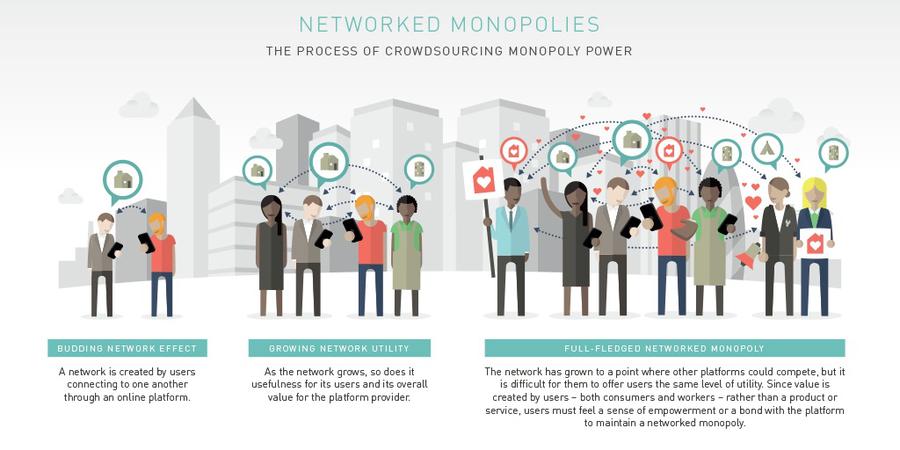

If these big companies, largely funded by venture capital, have the big money to venture into such tactics, the other side of the story, is that it is finally coming to mainstream consciousness how they should be considered as networked monopolies as researcher Bhrmie Balaram, 2016 calls them, and how deeply they rely on the network effect to scale. The interesting point Balaram raises is that the novelty brought by these companies is how they are so dependent on their users (both consumers and workers) and how they need to endow them with a certain kind of power. Consumers and users, have more power then they know!

Things are changing, and the pace of change is quicker than ever. In just one decade, iconic sharing economy companies such as Airbnb and Uber gained negative attention as being networked monopoly platforms (just as facebook and google…) hoovering up our data with no competition in front of them, whatsoever. People thus are becoming more more aware of the steps that should be taken to oppose this.

The City as A Space For Real Sharing

Regardless of all the criticism outlaid previously, the merit of the sharing economy is how it set the discourse, desire (and the materialization!) of the city as a place of real sharing. One important for the sharing city, in Neil Gorenflo, from Shareable, who set out to describe the 11 principles for sharing cities, which include solidarity, systems thinking, empathy, distributed architecture.

It seems that the possibility of an alternative sharing economy story… and REAL sharing city, has finally emerged. New and more inclusive forms of sharing that support the urban commons through community gardens, tool libraries, repair cafes and platform co-operatives are arising everyday. In a post published by the P2P foundation, Darren Sharp defines how sharing cities are about creating pathways for participation that recognise the City as Commons give everyone in the community the opportunity to enjoy access to common goods and create new forms of shared value, knowledge, and prosperity. And he tells us about the importance of this kind of vision as an alternative to the “the top-down, technologically deterministic vision of the future we so often hear about in discussions of Smart Cities and the Internet of Things – – a vision , he states, “dominated by sensor networks, data mining and myriad opportunities for corporate and government surveillance.”

A good example of how this new trend in sharing cities is gaining momentum is Christchurch, a city in New Zealand, where in the aftermath of an earthquake in 2011, an experiment in urban regeneration is being done. Another example is the Agrocité in the suburbs of Paris.

The discourse of sharing will definitely shape our cities in novel ways, so long we are attentive to the excesses of big companies acting under the same “sharing” umbrella, and we dare to act to find fairer alternatives.

Maria Fonseca is the Editor and Infographic Artist for IntelligentHQ. She is also a thought leader writing about social innovation, sharing economy, social business, and the commons. Aside her work for IntelligentHQ, Maria Fonseca is a visual artist and filmmaker that has exhibited widely in international events such as Manifesta 5, Sao Paulo Biennial, Photo Espana, Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Joshibi University and many others. She concluded her PhD on essayistic filmmaking , taken at University of Westminster in London and is preparing her post doc that will explore the links between creativity and the sharing economy.