It’s been almost one decade since the term sharing economy was invented to address a new way of doing business. Professor Lawrence Lessig was possibly the first one to coin the term, in 2007, when using it in a New York Times story about the Internet’s effect on work. Three years later Rachel Botsman’s book “What’s Mine is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption” popularised the term and movement “sharing economy”.

After almost one decade, every one knows what we are speaking about when we speak about sharing economy. Companies like Airbnb and Uber, two key companies seen as being part of the sharing economy movement, showed us, on its positive side, how it is possible to use peer to peer commons, to engage in exchange processes, extracting value from p2p production. As Michel Bauwens, from p2p foundation says,”that by itself, is already a recognition that peer to peer is a real thing.”

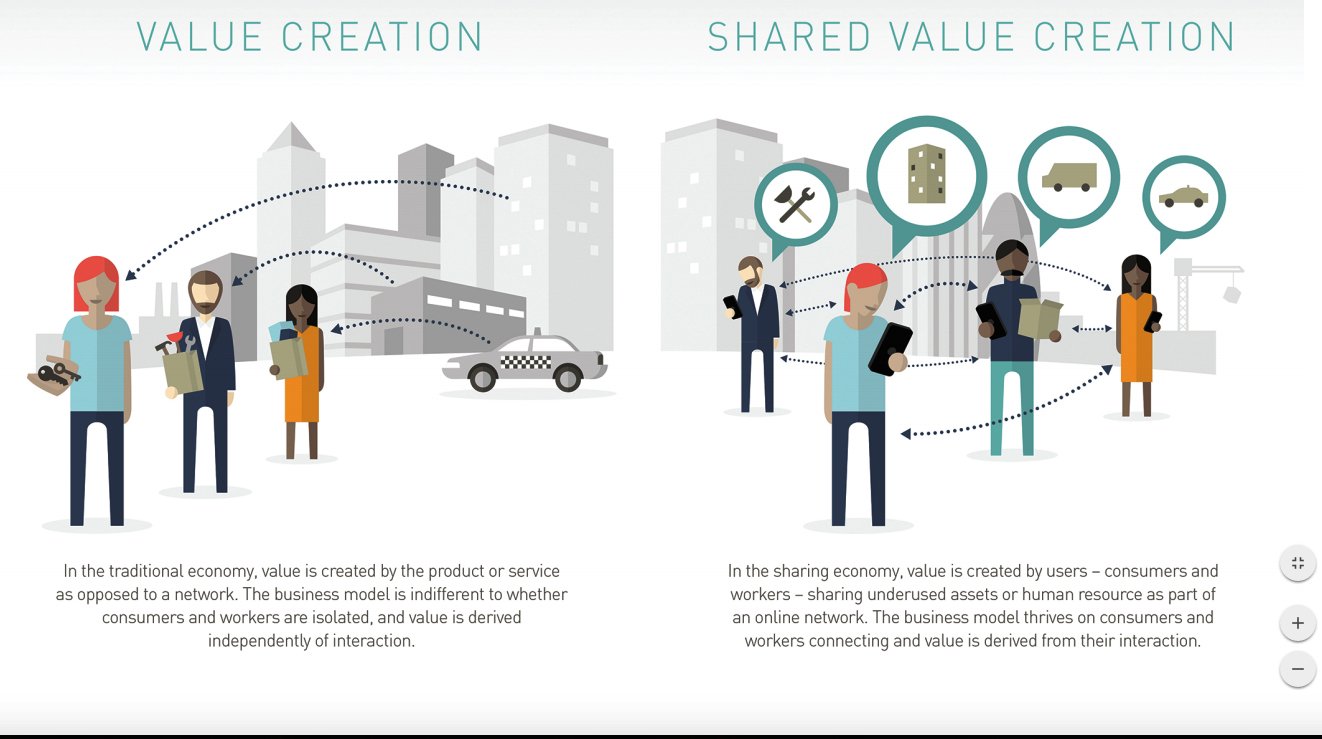

Uber and AirBnb, are examples of companies that are networked monopolies that depend on the value created by their users to keep expanding.The value they create is what Brhmie Balaram calls networked shared value. It is not based on resource extraction, but instead on helping the exchange of resources.

The radical novelty of the sharing economy is that users are the ones who create value. Both consumers and workers achieve this by sharing access to underused assets or human resources in an online network. Users do have some power over technology to change their lives and work.

Unfortunately the most known “sharing” economy companies, are not reinvesting in the human capital. Its monetization is extracted by corporations that do not reinvest in the reproduction of the system. This unfair reality is bringing precarity in terms of labour. As Michel Bauwens points out, paradoxically, peer production produces a form of hyper liberalism. Large corporations don’t even need to pay people anymore.

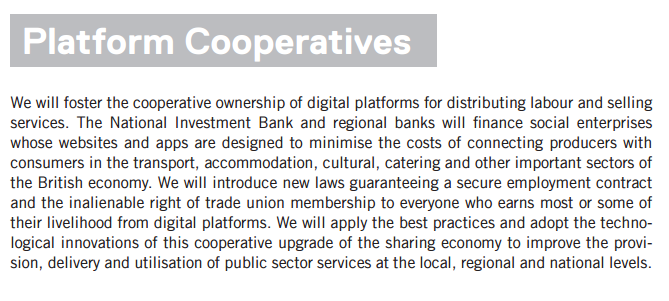

As more and more people become aware of this, important questions are raised, that try to find answers to solve this issue. Trebor Scholz , an associate professor of culture and media at the Eugene Lang College of the New School for Liberal Arts, wrote recently an important text where he asks us to ponder “Why do its owners and investors have to be the main benefactors of such platform-based labor brokerage?” In his text, entitled “Platform Cooperativism vs. the Sharing Economy” he proposes a solution: Platform Cooperativism.

According to P2P foundation, platform cooperativism can be defined as “worker–owned cooperatives designing their own apps-based platforms, fostering truly peer-to-peer ways of providing services and things”. The basic model proposed is that those that offer the greatest value for such platforms should also own and control them, i.e. users!

The platform cooperativism movement is still in its infancy. It began two years ago, at the SHARE conference in San Francisco in 2014, when Janelle Orsi, executive director and co-founder of the Sustainable Economies Law Center, challenged corporate sharing companies to share their ownership and wealth with users. Her challenge led Trevor Scholz and then Nathan Schneider, a scholar in residence of media studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, to research and write about Platform Cooperativism, giving us many concrete examples of various types of platform cooperatives, a few of them using blockchain technology. Both authors raised the topic of Platform Cooperativism to a global audience, as its evident, for example, in Jeremy Corbyn’s document Digital Democracy Manifesto, where support for Platform Cooperatives is clearly outlined.

What could be some example of Platform Coops? From babysitting to data, images or car sharing, all kinds of platform cooperatives could be made.

Examples Of Platform Coops

TimesFree

TimesFree was created in Helen Nissenbaum’s class. It is a blockchain based labor system based on cryptocurrency. TimesFree is a Babysitting co-op that is a great model for the peer economy. The app uses a form of scrip, a token system, that allows people to share between themselves without using money. In these, a single token is worth 15 minutes of babysitting. Others just have a central log or spreadsheet, with a member acting as a secretary. Families who use these can save thousands of dollars every year, even if they just use it a few hours a week.

Data Commons Co op

The Data Commons Co-op is “perhaps the geekiest of all cooperative organizations on the planet!” The Data Commons Co-op greases the flow of data between communities in the sharing economy. The co op prefers to call the sharing economy, humorously , “cooperative, solidarity, new, call-it-what-you-will economy.” Its members are cooperative development centers, federations, solidarity economy groups, and others, who want to maintain robust, accurate, useful platforms for sharing information. The co-op not only serves these communities, it is owned by them.

Fairmondo

Fairmondo is a cooperatively owned online marketplace where you can get ethical goods and services from sellers with a strong commitment to ethical business and trade. It is like an eBay which is ethical. Its marketplace is cooperatively owned and run by its users: buyers, sellers, workers, investors. Fairmondo was originally launched in Germany in 2012 as a cooperatively-owned marketplace to promote fair goods and services as well as responsible consumption. The Fairmondo team has created a federated model in which an affiliate can launch a co-op in another country using the Fairmondo brand and platform to serve the local market.

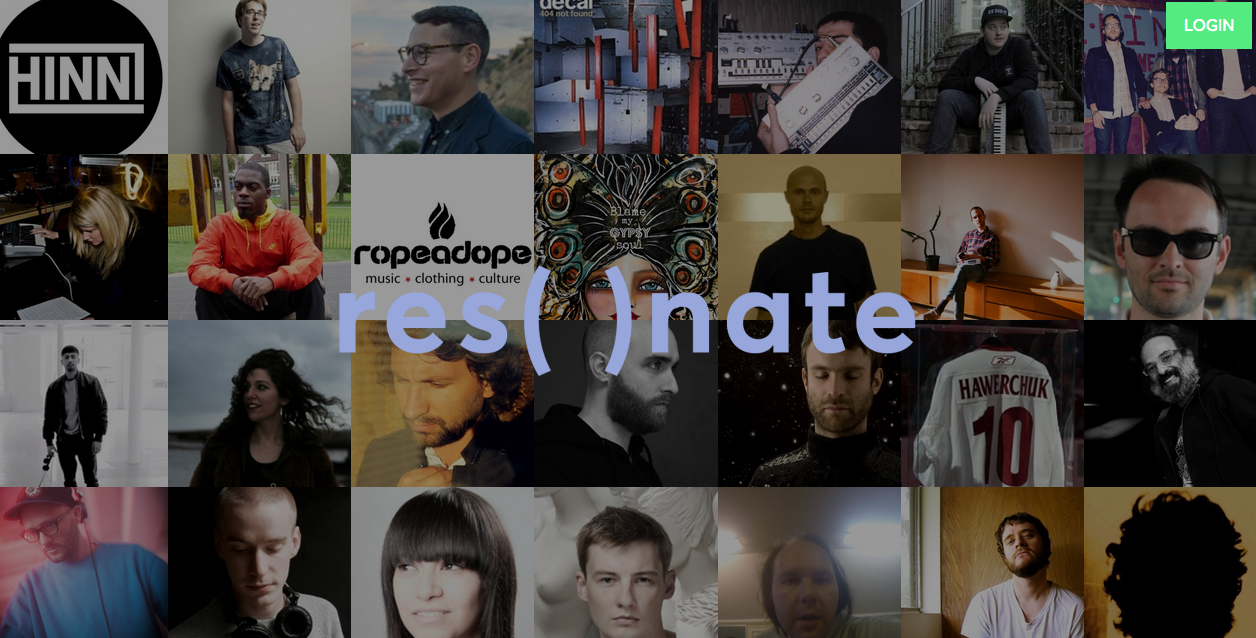

Resonate

Resonate is a streaming music service cooperative owned by the people that use it – musicians, indie labels, fans + developers. The platform is blockchain-based, and unlike other streaming companies, it is a direct-to-artist and pay-as-you-listen. Its goal is to be able to pay artists up to 2.5x more than its competitors, while also offering better data and management tools.

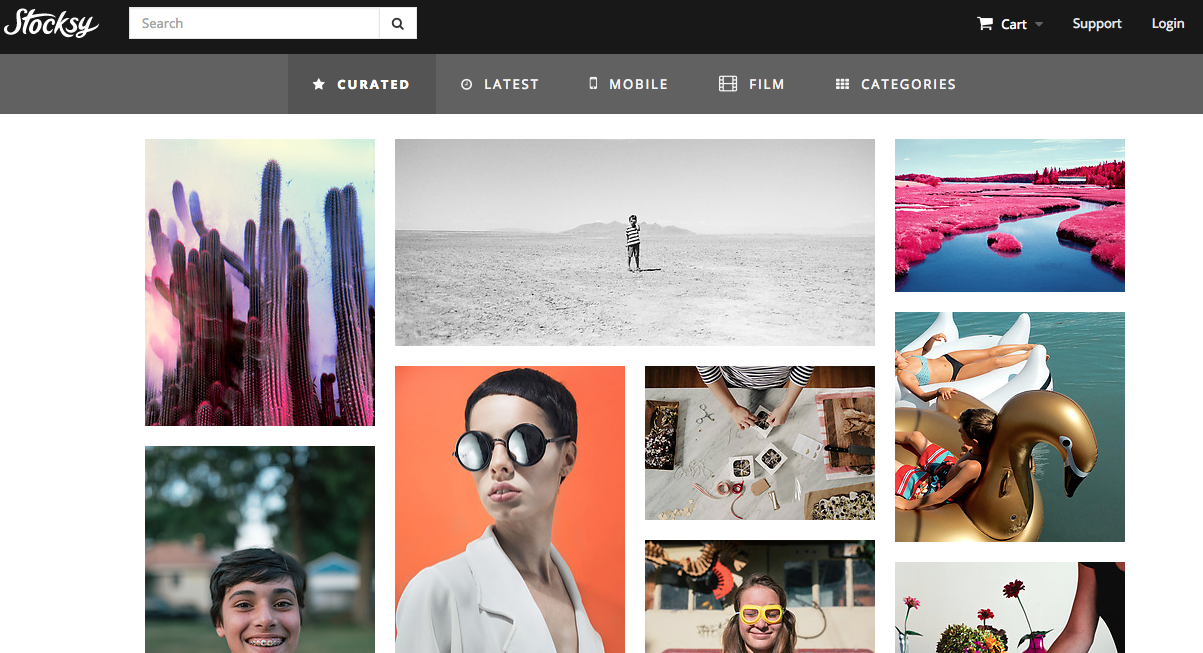

Stocksy

Stocksy is an artist-owned cooperative that sells stock-photography. The co-op is based in Victoria, British Columbia, and is built on the idea that the artists who contribute photos to the site should receive fair pay and have sustainable careers. Artist-members license images to Stocksy and receive 50 percent commission on sales and share any surplus-income at the end of each year. The co-op was created after the founders sold their previous venture, iStock, to Getty Images. By 2014 Stocksy had a revenue of $3.7 million, and over time, it has paid several million dollars in surplus to its artists.

Maria Fonseca is the Editor and Infographic Artist for IntelligentHQ. She is also a thought leader writing about social innovation, sharing economy, social business, and the commons. Aside her work for IntelligentHQ, Maria Fonseca is a visual artist and filmmaker that has exhibited widely in international events such as Manifesta 5, Sao Paulo Biennial, Photo Espana, Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Joshibi University and many others. She concluded her PhD on essayistic filmmaking , taken at University of Westminster in London and is preparing her post doc that will explore the links between creativity and the sharing economy.